I remember taking a call on-air one Mothering Sunday from a women who said I'd made her cry.

There she was, at the bottom of the garden pruning her flowers, telling me she'd cried when she'd heard a single dad call in earlier. He'd related the story that his daughters had sent him a Mothers Day card to say he'd, effectively, been the best mother they could have wished for. The women explained that she'd lost her husband a fortnight before, and not allowed herself to mourn; yet the unrelated tale on-air from a chap she'd never met left her shedding the tears she so needed to cry. As is so often the case with grief, it is displaced and hits you when you least expect.

How incredible it is that it was the mass broadcast medium of radio which brought out the Kleenex that sunny Sunday morning. For her, this was not about radio, this was about a friend in her life. Talking to her. Connecting. Being there.

I am not the only person in radio who's received calls from listeners on the darkest days of their lives . When it seems there is no-one else they feel they can open up to; they choose radio. Sometimes a presenter they relate to, but other times just a random text to 'the station'. And it's just as often a music station as not.

A few years ago, I called a listener back off-air who was caught up in a terrible situation and threatening a dramatic exit. I listened; and thankfully was able to help those better qualified than me track her down to assist. About a year later, she called again, sounding bright-eyed and bushy-tailed, to say thanks. Radio had helped her to get her life together.

Maybe the best definition of radio is as a friend. Yes, it may sound like a hackneyed word from a 1980s jingle package, but it's as true now as it was then. Chris Moyles' 21st Century audience would readily have viewed him as their 'mate'. It enjoys that peculiar position of feeling utterly close and personal; whilst dirty great big aerials pump out its charm efficiently to millions at low cost.

Radio is not always about helping you through tough times. But is that not like a friend too?

Good friends are sometimes serious, sometimes not. The best ones are life and soul of your party, yet also there to fetch you from the airport at 5 am in your hour of need. Most research suggests that the key driver for much radio listening is that it 'lifts my mood', but there is also that reassurance that if you need to know anything, the trusted radio will tell you. Until that time, you can relax knowing the world is well. Just like friends, sometimes the relationship is intense; other times they are just there. Rather like the contrast between active late night or breakfast radio; and more passive daytime.

Good friends are sometimes serious, sometimes not. The best ones are life and soul of your party, yet also there to fetch you from the airport at 5 am in your hour of need. Most research suggests that the key driver for much radio listening is that it 'lifts my mood', but there is also that reassurance that if you need to know anything, the trusted radio will tell you. Until that time, you can relax knowing the world is well. Just like friends, sometimes the relationship is intense; other times they are just there. Rather like the contrast between active late night or breakfast radio; and more passive daytime.

Aren't the greatest friendships in life the ones where, even after months apart, the conversation flows as if you last saw them the day before? You pick up as you left off. That is a beauty of radio: it's always there; and the formatics ensure you know the station's personality will be the same next time you bump into it.

In any definition of radio, real-time might be one important factor. Most radio is consumed as it is broadcast. Even wholly voice-tracked stations enjoy a sense of time and place.

This emotional, accessible medium also connects. So much great breakfast radio today is about story-telling. A person on the radio will share the ups and downs of their own life and their listener will relate. Few radio presenters portray themselves as perfect. Ask Paula White.

A friend introduces you to things too: a new trend, film, fashion or song. That's another of radio's great qualities. In a world of ever-growing choice, we need someone to guide us through. To help us marshal our music listening and harvest our news. It's great arriving in a new city, but much better if there's someone to show you round. Even the cleanest of formats have a friendly voice and someone who seems to know the sorts of songs you like.

This is a friend which lives and breathes. It has a spirit. A character. And a name.

This is a friend which lives and breathes. It has a spirit. A character. And a name.

It's interesting that when looks at the biggest media stories on the last decade, for good or for ill, they are about radio. Whether the Andrew Gilligan Radio 4 interview; the Ross/Brand debacle; or the Royal 'prank call', they are about radio. When the DG of the BBC resigned, it was probably the Radio 4 interview by Humphrys which was credited with being one of the final pieces in that uncomfortable jigsaw. A hundred years on and the medium of radio remains the one which creates the headlines. The unwashed simplicity and agility of the medium combine to great effect; and in the interview situation, the intimacy through the single dimension of voice exposes the truth effortlessly.

Every day, every presenter will connect with their audience. Sometimes that connection is a smile. Very frequently too, it's a tangible response, a phone call, a text, or a social media exchange. Pick up any listener email today and study the language. It is the language of a friend writing to a friend. Yes, the talk stations will generate probably more response, but good music presenters on decent stations now will readily agree that they have a friendship with their audience. And their audience would agree.

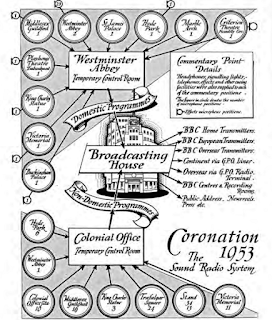

As the world changes, it's certain that others will indeed trespass in radio's garden, just as TV once did. There will be a shift, but as the Observer newspaper correctly said of radio in 1953 after TV's Coronation coverage "For sound radio, no flowers yet". Many of us recall the scare stories when the primary-coloured breakfast TV kicked in back in 1983. At the time of ILR's inception, there was also the fear of the radio-cassette player. But, it's tough still to envisage a total substitute for a medium which 90% of people consume for over 20 hours a week, given the affection listeners show towards their radio.

Sometimes when one struggles for a definition, it's useful to consider the inverse. What radio isn't. Or maybe how much you'd miss it if it wasn't there. Ask any programme director who's dared to change a schedule, presenter or station name, or close a station to proffer an answer to that.

The question of 'what is radio' falls into ever sharper focus as music streaming services multiply and press and conference coverage amplifies their existence. Maybe there is no clear answer to the conundrum. Is a flow of great songs streamed at will radio or not? Is the Media Guardian's elegant podcast a radio programme or not?

Just maybe there is no glib black and white answer. Just as Freud suggested that sexuality lay on a continuum, maybe radio is the same. Some sorts of sound are just more like radio than others.

Consider too the dictionary definition of radio remains about carriage not content. We have, however, chosen to adopt the word 'radio' as shorthand for 'radio programming'. Maybe, today, we should frame a new definition for submission to the OED.

The contradictions of radio are likely part of its attraction. It's perfect, yet imperfect; surprising, yet consistent; active, yet passive; talking, yet musical; amusing, yet serious; personal, yet huge; trite yet life-saving. It's a friend and it's alive.

Read too Phil Riley's blog. Should we be worried about Apple?

And Mark Barber's analysis (RAB) of 'how to tell if your streamed music service is radio'.

Consider too the dictionary definition of radio remains about carriage not content. We have, however, chosen to adopt the word 'radio' as shorthand for 'radio programming'. Maybe, today, we should frame a new definition for submission to the OED.

The contradictions of radio are likely part of its attraction. It's perfect, yet imperfect; surprising, yet consistent; active, yet passive; talking, yet musical; amusing, yet serious; personal, yet huge; trite yet life-saving. It's a friend and it's alive.

Read too Phil Riley's blog. Should we be worried about Apple?

And Mark Barber's analysis (RAB) of 'how to tell if your streamed music service is radio'.